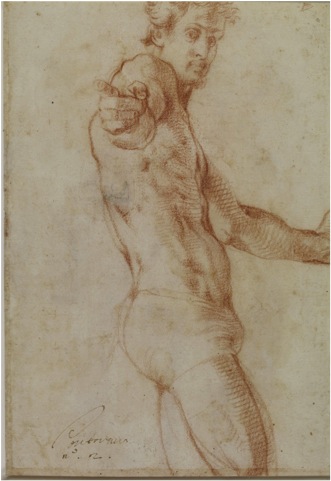

Pontormo drew himself naked whilst escaping from the plague. For a few months in 1523-4 he was holed up in a Carthusian Monastery, the Certosa di Galluzzo, a few miles outside Florence.

The first intimations of a wave of plague had come in August 1522, when five officials were appointed to protect Florence from the disease that had already hit Rome, and was currently raging in the countryside around the city. The Florentines closed the gates to incomers, but to no avail. Blamed by some on an anonymous “German” incomer (because xenophobia, racism and infectious disease often go hand in hand), the plague soon had a grip in the district around the church of San Lorenzo. The streets were sealed off and the disease burnt itself out by the end of November, with the relatively low death rate of around 20 people.

Unfortunately for the Florentines, the plague came back into the city in early 1523, and in March of that year the government decreed that no-one could leave Florence, in an entirely unsuccessful attempt to stop upper classes abandoning the city. All those affected by plague – largely in the poorest areas at the edge of town – were made to go to the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, and if anyone in their households had remained healthy, they were kept in quarantine in the Camaldoli monastery. The stopping of normal life in the city lead to riots in May, as the poor who didn’t have the plague started to die of starvation due to having no work and no money. By July, it was estimated that around 3000 people had died (from a population of around 60,000, so about 5%), but by 1st August 1524 the plague had largely died down.

Although Florence got off relatively lightly in comparison to some other cities (in Rome, it was reckoned, 25,000 people died), we should not underestimate just how profoundly frightening this disease was. Sam Cohn and Guido Alfani’s work on the 1523 plague in Milan indicates that the symptoms included buboes and tumors, often accompanied by black or purple spots, but the single most defining characteristic was rapidity of death. More than half of those affected died on the day they saw their first symptoms. Throughout the century, the modal time the plague lasted was two days. The renaissance saying, often found on wills, that “nothing is as certain as death, nothing as uncertain as the hour of death” seems less morbid introspection and more simple statement of fact when considered in this light.

Pontormo’s former teacher, the imaginative, flamboyant and brilliantly eccentric painter, Piero di Cosimo, had died during the first wave of plague in 1522, leaving his favourite pupil his house in via Larga. No wonder Pontormo took the chance to run away when he could.

Self-isolation at Galuzzo

The Charterhouse at Galuzzo was the perfect place for practising social distancing (a phrase that I’ve come across often over the last few coronavirus-dominated days). Not only did their statutes demand that their monastery be built in remote locations, so the monks remain free of all distraction by the world, but monks lived individual, hermit-like existences. Occupying two-storey cells disposed around the large cloister, each monk had access to their own small enclosed garden which they were expected to tend. Food and other necessities, were brought to the monks by lay brothers who left them in a turntable hatch in the wall. Once a week, walks were taken in the countryside, and monks were permitted to talk to each other on these occasions, walking in pairs and then swapping partner. It might be that the drawing of two monks on the other side of the paper to the self-portrait drawing (see the image here) was done on such an occasion. The Carthusian constitutions, restated in 1509, urged brothers to:

ponder and reflect on the great spiritual benefits derived from solitude … and you will readily agree that for tasting the spiritual savour of psalmody; for penetrating the message of the written page; for kindling the fire of fervent prayer; for engaging in profound meditation; for losing oneself in mystic contemplation; for obtaining the heavenly dew of purifying tears — nothing is more helpful.

Pontormo and Dürer

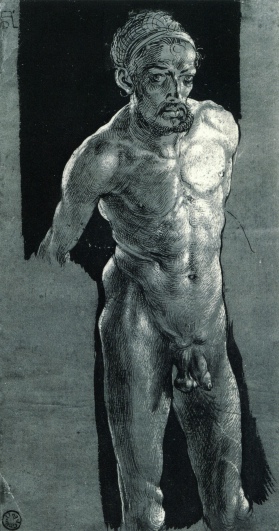

Pontormo’s self-portrait drawing is very unusual. I don’t know of any other Italian examples of a nude or semi clad self portrait. The one other image that really seems to correspond to this is a couple of decades earlier and German – Albrecht Dürer’s incredible naked self portrait now in Weimar. There is a similar viewing distance, angle and truncation at the knees as Pontormo’s version – but there are more than superficial resemblances. Erwin Panofsky suggested that Durer’s self-portrait should be connected to a wave of epidemic illness that had been spreading through Germany, Dürer forensically (and unapologetically) examining his disease-raddled naked body. Both he and Pontormo had by this time become adept in creating idealised nude male figures, all muscles and poise, blank-faced everymen. What did it mean to memorialise their own bodies like this? Both drawings can best be understood perhaps, as the result of long periods of introspection in the face of existential panic brought on by an epidemic. They each possess a similar air of self-speculation, of asking difficult questions about the relationship of the body to the self, of the general ‘nude’ to the individual ‘naked’, of confronting one’s own mortality. We can possibly see in Pontormo’s work a mixture of a search for symptoms, a kind of memorial, a meditation on physicality and – with his right finger pointing at the viewer (or at himself in the mirror? or a sizing gesture?)– possibly a reminder that he so easily could be next.

Thank goodness Pontormo fled the plague. Had he died in 1524, he would never have completed his paintings of the Capponi Chapel, one of the most incredible decorative ensembles of the early sixteenth century. When Italy is open to visitors once again, you should go to Florence to see it. Head over the Ponte Vecchio but pause before joining the crowds at the Pitti Palace, and go into the church of Santa Felicità. Just to the right of the entrance, you’ll see the chapel and its luminous inhabitants.

There’s a lot to see and think about here, but before the intellectual pondering kicks in, before you turn your reactions into words, just lose yourself in the Deposition altarpiece, with its mass of candy-coloured figures, circling in sadness about a central void. The Virgin Mary has fallen backwards, her loss proving too heavy to bear, as her son, Christ, is led away by mourners. That emptiness at the centre! Pontormo, fresh from his self-imposed exile in Galluzzo somehow portrayed his grief and loss in that swirling composition. He reminds us that facing death, disease – and fear of both – is part of our shared humanity.

Written with love to my friends in Italy.

Leave a comment